Blog posts

Integration of Risk Phenotypes Stratification Models as part of Smart Early Warning Clinical Decission Support in CAREPATH

Published on 21 June 2024The risk of adverse events in older adults, named mortality, incident disability, hospitalization, emergency visits, institutionalisation, poor quality of life or increased healthcare costs, varies based on common aged-related conditions like frailty, specific diseases, multimorbidity or cognitive situation [1]. However, this risk appears to differ when considering the severity of chronic diseases and conditions. The gap in knowledge about the relationship of multimorbidity patterns, frailty, disability and cognitive situation with adverse outcomes in older adults is still not well understood, and there might be interactions on how different configurations produce different outcomes.

Multimorbidity has been quantified in several ways, such as simple count of conditions, weighted count, specific comorbidity indices, or groups of individuals who have similar multimorbidity patterns using latent class analysis [2]. These patterns have been associated with quality of life, functioning, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits [3]. Rather than simple counts or weighted comorbidity indices, multimorbidity patterns may be more suitable to examine clinically relevant subgroups within older individuals with the same multimorbidity burden and frailty status. In addition, including frailty, disability, and cognitive status to this approach is new and may enrich the predictive power to detect poor healthcare outcomes in vulnerable populations.

Considering both multimorbidity patterns and frailty is important for identifying older adults at greater risk of adverse events, because increasing levels of frailty are associated with an additional burden of individual service use, while older adults with mild and moderate frailty contribute to higher overall costs [4]. In addition, neuropsychiatric class has also been associated with lower survival across all frailty levels [2].

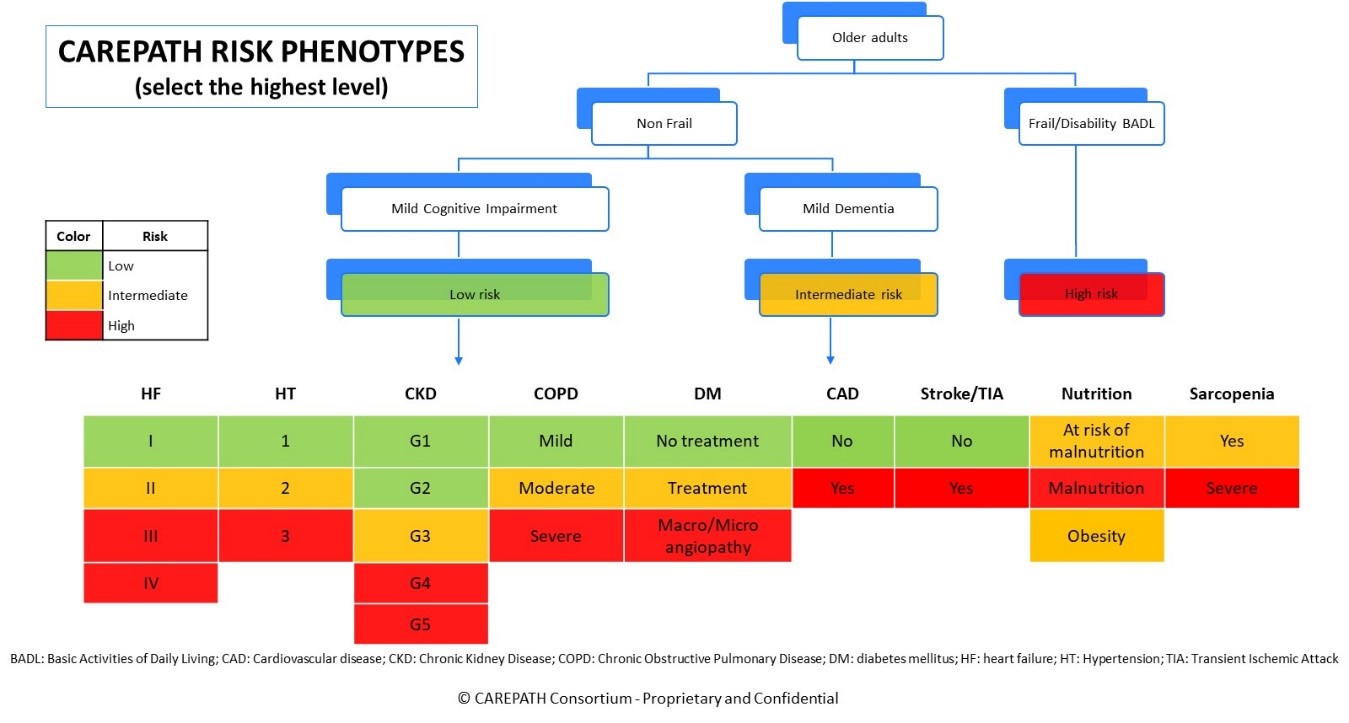

The CAREPATH Clinical Research Group conducted several meetings and a literature review to calculate the overall risk of a patient based on the selected risk phenotypes. The conditions included in the risk analysis were frailty status, disability in basic activities of daily living (BADL), cognitive profile, hypertension (HT) grade, heart failure (HF) stage, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) stage, chronic kidney disease (CKD) grade, diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary artery disease (CAD), presence of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), nutritional status and sarcopenia (see figure below).

Risk phenotypes were first hierarchical based regarding frailty/disability, followed by cognitive profile. Older adults with frailty or disability in BADL were considered high risk od adverse healthcare outcomes based on previous research, and non-frail or robust older adults were subclassified in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (low risk) and mild dementia (intermediate risk). After this first classification, older adults are categorized in low risk (green), intermediate risk (yellow) or high risk (red) regarding the multimorbidity profile including the aforementioned diseases. Finally, older adults are categorised in the three risk phenotypes using the highest risk at any point of the figure.

This classification is new and empirical, although based in the clinical expertise of the Clinical Research Group and the literature review conducted for the CAREPATH clinical guidelines. In CAREPATH, risk profiles will be used by the healthcare team to determine early warnings and alerts and will be incorporated in the Clinical Decision Support Modules. Finally, one of the objectives of CAREPATH will be to clinically validate this new risk phenotype rules. Using clinical outcomes from the clinical investigation and multisensory data collected by the AICP, we will conduct artificial intelligence (AI) analysis to determine if these rules provide a valid and reliable pre-test approach to the healthcare provision of multimorbid older adults with MCI or mild dementia.

Bibliography

- Ogaz-González R, Corpeleijn E, García-Chanes RE, et al. Assessing the relationship between multimorbidity, NCD configurations, frailty phenotypes, and mortality risk in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2024; 24: 355.

- Nguyen QD, Wu C, Odden MC, et al. Multimorbidity Patterns, Frailty, and Survival in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019; 74: 1265-70.

- Olaya B, Moneta MV, Caballero FF, et al. Latent class analysis of multimorbidity patterns and associated outcomes in Spanish older adults: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2017; 17: 186.

- Fogg C, England T, Zhu S, et al. Primary and secondary care service use and costs associated with frailty in an ageing population: longitudinal analysis of an English primary care cohort of adults aged 50 and over, 2006-2017. Age Ageing. 2024; 53: afae010.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s

Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant

agreement No 945169

This project has received funding from the European Union’s

Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant

agreement No 945169